© 2013 Michael Coghlan, Flickr | CC-BY-SA | via Wylio

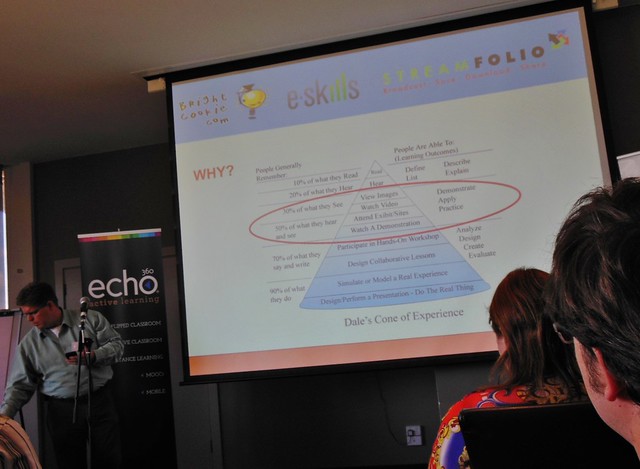

We’ve all heard about or seen the perspective of the so-called “Dale’s Cone of Experience” that says:

“We learn 10% of what we read, 20% of what we hear, 30% of what we see, 50% of what we see and hear, 70% of what we say or write…..[and] 90% of what we teach.”

I had originally heard that it was developed by William Glasser, but then learned from his organization that, though he had described it as an accurate reflection of his own experience and sometimes described it as such, he did not originate it nor would he vouch for specific research backing it up.

A few years ago, while searching online, I discovered that, in fact, there wasn’t research specifically supporting those percentages.

Now, a group of people who have apparently been making a major effort over the years to point this fact out have written four articles documenting how they say it’s been misused over the years.

Yawn

I’m sure they’re right about the inaccuracy of the specific percentages, and I agree we should throw out the Cone. But there is an enormous quantity of research that supports the idea that constructivism is substantially more effective than lecture or direct instruction for student learning. Here are links that research:

The Best Posts Questioning If Direct Instruction Is “Clearly Superior”

The Best Research Demonstrating That Lectures Are Not The Best Instructional Strategy

“What I Cannot Create, I Do Not Understand”

Important Study: “Expecting to teach enhances learning, recall”

So, sure, spend a little time stomping on the Cone if you feel like it. But spend a whole lot more time conveying and acting on its research-supported main message — that “learning by doing” is the way to go…

Hey, Larry, I have to admit, I’m a little puzzled at your flippant attitude about this. Dale’s Cone of Experience has been cited in some pretty significant research works as some sort of research-grounded source, when Dale used no actual research to create the cone and arbitrarily made up the percentages. It was largely intuitive. The issue isn’t whether or not the Cone conveys generally accurate principles, it’s the authority that continues to be given to it, particularly when it appears in a bibliography. When a researcher or speaker or whomever cites Dale’s Cone as a scholarly source, it brings the authority of any other sources cited into question. Maybe it’s my mindset because I’m writing a dissertation right now, but this is kind of a very big deal in my book.

Randy,

I agree, as I said in the post, that the Cone’s lack of research support should be pointed out. I just think that after you point that out, little is gained by piling it on. Point it out, and then, I believe, showing the research support for its basic perspective is a more productive use of everybody’s time.

Larry

Larry,

But what if real research leads to a different conclusion? If you conduct research in order to support intuition, you don’t end up with good data because non-supportive information is ignored. That may be what Randy was getting at.

Possibly. But the research for constructivism is just so overwhelming these days — I usually post a new study about it every month

Your cherrypicking research that supports your belief. What research actually shows is that construvist teaching is a bad idea for novices, but works for learners who have reached a certain level of proficiency.

I have shared extensive research supporting my position. Feel free to do the same.

Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching, (Kirschner, Sweller, Clark)

Albanese, M., & Mitchell, S. (1993). Problem-based learning: A review of the literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Academic Medi- cine, 68, 52–81.

Anthony, W. S. (1973). Learning to discover rules by discovery. Journal of Educational Psychology, 64, 325–328.

Ausubel, D. P. (1964). Some psychological and educational limitations of learning by discovery. The Arithmetic Teacher, 11, 290–302.

Berkson, L. (1993). Problem-based learning: Have the expectations been met? Academic Medicine, 68(Suppl.), S79–S88.

Colliver, J. A. (2000). Effectiveness of problem-based learning curricula: Research and theory. Academic Medicine, 75, 259–266.

Cooper, G., & Sweller, J. (1987). The effects of schema acquisition and rule automation on mathematical problem-solving transfer. Journal of Educa- tional Psychology, 79, 347–362.

Thanks, Jan. However, most of your citations are pretty old. Anything more recent?

Yes, there are some more recent sources that discuss this.

First, though, I looked at the links you posted above, but saw that they were mainly critical of lecturing (rather than direct instruction) as a teaching method. And, I happen to agree with you that lecturing leaves a lot to be desired as a teaching method and that other methods are superior, so I’m not going to include anything about that (though I did read a paper published in 2014 that found that people remember less of what they hear than what they see or touch [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089914]).

Now, on to other articles:

* A 2019 piece in “Aero” Magazine titled “The Problem with Constructivist Teaching Methods,” summarizes a number of articles and papers (along with a book) that go over the many problems with constructivism (and also includes links to view them), before concluding, in the final paragraph, “Constructivist teaching methods are highly ineffective…”

You can read it here: https://areomagazine.com/2019/01/22/the-problem-with-constructivist-teaching-methods/

* The 2009 edition of “Visible Learning” by John Hattie indicates, first, that constructivism is a theory of learning rather than teaching (pages 26 and 243); and, second, that methods that require the teacher to more directly guide the class (e.g. direct instruction, mastery learning) are above-average in effectiveness, while ones that have the teacher serve as a facilitator and do less guidance (like problem-based learning and individualized instruction) are below-average in effectiveness.

An updated list showing various effect sizes can be found here: https://visible-learning.org/hattie-ranking-influences-effect-sizes-learning-achievement/

* Barak Rosenshine’s 2012 article in American Educator (“Principles of Instruction”) lays out teaching techniques that have been shown to work — and they all require the teacher to take an active roll in class (rather than serve as a facilitator). They were based on research on cognitive science, how master teachers practice their craft in the classroom, and research about cognitive supports that make it easier for students to learn.

You can see it here: https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Rosenshine.pdf

(He also wrote a booklet in 2010 that went over the same points, though, given that it’s longer than the 2012 piece he wrote, it likely goes into more detail. Here is a link to it: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/Educational_Practices/EdPractices_21.pdf)

* Britain’s Sutton Trust released a booklet in 2015 titled “Developing Teachers” that went over research-backed teaching strategies that worked. Ones they stated worked well included the teacher understanding the subject they were teaching, various teaching practices (such as feedback, assessment, reviewing, and using scaffolding to introduce new materials, among others), and classroom management. Meanwhile, they stated that practices like discovery learning, learning styles, and the learning pyramid, do not work well.

You can read it here: https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Developing-Teachers-1.pdf

* In 1996, Adams and Engelmann wrote a work that went over direct instruction in detail, including what it is (introduction and chapter 1), features of programs that use it (chapter 2), and debunking myths about it (chapter 3).

You can read it (and access said files in their entirety) by clicking on this link: https://www.nifdi.org/docman/suggested-reading/book-excerpts/research-on-direct-instruction-25-years-beyond-distar-engelmann-adams-1996

Later, in the 2009 edition of “Visible Learning,” John Hattie referred to their work on direct instruction (page 205) and summarized the steps for doing it (pages 205-06).