I sent this tweet a couple of days ago:

These last three years have been the most challenging of my teaching career – even more challenging than my first year. How common of a feeling do you think this is among teachers in general?

— Larry Ferlazzo (@Larryferlazzo) February 14, 2023

Though I expected to get a few responses, I certainly didn’t expect to received the hundreds of replies and “likes” along the lines of “Yes, we all feel this way and it’s good to know we’re not alone” (click on the tweet to see them all). Teachers tweeted about student behavioral challenges, political attacks, academic setbacks due to COVID, student mental health needs, pressure to “accelerate” learning, lack of staff like custodians and bilingual aides, the need for even more than typical differentiation, and the sense of desperation that “there is no end in sight.”

Of course, this shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone. Countless surveys have shown huge percentages of teachers contemplating leaving the profession, teacher job satisfaction is at a fifty year low (see Depressing Statistic Of The Day: Lots Of Teachers Are Not Happy), and the numbers of students entering teacher-prep programs have been declining.

Some education pundits pooh-pooh the idea that many teachers will actually leave the profession, but that perspective misses an important point, which I made last week in this tweet:

And all those non-teacher education pundits out there who pooh-pooh this by saying that most will actually end up staying ignore how much staying at a job you feel you want to leave will impact teacher morale and how much energy can be given to students https://t.co/7a1skIxiX1

— Larry Ferlazzo (@Larryferlazzo) February 11, 2023

If I’m feeling burnt-out, and I teach in an almost ideal situation – supportive administration, teaching classes I want to teach and what I want to teach in them, great students, no one bothers me, in California where I don’t have to worry about books in my classroom library being banned or about being attacked when I do lessons on systemic racism – I can only imagine how teachers feel who work in more difficult school environments.

So, if district leaders, school administrators, politicos, and/or the general public wanted to do something about this teacher morale crisis, what could they do (keeping in mind the true saying that “teacher working conditions are student learning conditions”)?

Here are a few ideas, and I’d love to hear more:

- Public acknowledgement by non-teachers, including district leaders, that the teaching environment is more difficult and that things are not “back to normal.”

- Creating paid-time for professional development in areas identified by teachers and provided by teachers. And not adding those sessions to the teacher work-day. Instead, creating time during the school day.

- Substantially increasing the pay for substitute teachers so that people want to be subs. One way to do this would be to hire a permanent pool of teachers as full-time substitute teachers. It’s not possible to overstate the crisis the lack of subs is for teachers – not only does it mean professional development options are eliminated (because there is no one to replace teachers during those days), but it means that regular teachers are losing their planning periods to cover for their colleagues who are out because subs can’t be found.

- Increasing teacher salaries. Teachers earn about twenty-percent less than other professionals with similar education levels. Too many teachers work at other jobs to make ends meet.

- Districts providing funds to schools to hire local residents, who have relationships in those communities, to contact and work with families and their children who are experiencing challenges in schools.

- Stopping attacks on LGBTQ students and teachers; putting an end to book banning campaigns, and getting over Critical Race Theory hysteria.

- Creating time for “Advisories,” where teachers and other school staff can spend specifically allotted time with students on non-academic subjects like Social Emotional Learning.

- Districts working with teachers to figure out genuinely effective ways to support new teachers instead of the generally useless and paperwork-driven district programs that exist now.

- Districts working with teachers of color to develop specific strategies for supporting them and recruiting more.

- Providing stipends to teachers who want to develop and participate in book clubs focused on pedagogical issues.

- Districts actually asking teachers – through their unions where they exist – for ideas on how to spend money and actually listening to them.

- Creating more time during the school day where teachers can plan and assess so they don’t have to take so much work home with them.

- University teacher-prep programs seriously re-evaluating if their programs are truly readying their students for this new classroom environment.

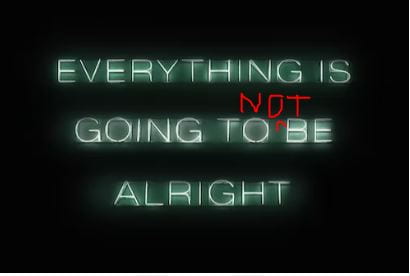

District leaders and public officials don’t have a great track record of responding to the concerns of educators, so I’m not holding my breath that most – if any – of these ideas will get widely implemented.

And, if that’s the case, I think a lot of people are going to be surprised about the long-term price everyone is going to have to pay when there are fewer educators, and more demoralized ones, supporting today’s and tomorrow’s children.

Recent Comments